Trip 48

November 2, 2024

We had several possible activities planned for today, including the Archaeology Museum.

The museum adjoins the National Library and the meeting place for the Irish Parliament . The museum was built in the 1890’s and its classical style reflects the Roman and Greek displays it originally held. Now, though, it’s dedicated to the history of Ireland.

We were lucky to have entered just as a guided tour started and this tour took us through several sections of the museum, focusing most on the role and history of the Vikings in early and medieval history.

The first recorded Viking raids on Ireland took place in 795 AD, when islands off the north and west coasts were plundered. Later on, Viking fleets appeared on the major river systems and fortified bases for more extensive raiding are mentioned from about 840AD. Monasteries were one of the main targets of Viking raiders because they were likely to contain valuable loot and most importantly, people to be sold as slaves. One small scale replica of a type of ship built by Vikings shows the shallow draft in shallow waters, of the ship, important when navigating rivers. This was not one of their longships though. Longships were all made out of wood, with cloth sails (woven wool). The replica below was actually sailed from Ireland to Newfoundland by the archaeologists who built it.

At the time of the Viking invasions, Ireland was mostly rural, with small settlements and no large cities. You can only imagine the terror when natives saw longboats coming up the rivers. Viking longships could vary in size and crew capacity: the average longship could hold up to 25-30 crew members. Larger longships had crews that were composed by about 40 members, while the biggest longship ever found, named Skuldelev 2 had space for a crew of 70-80 people.

Dublin appears to have been founded twice by the Vikings; first as a trading emporium or longphort at which the Scandinavians overwintered from the 840s onwards. This settlement was probably located on the south bank of the Liffey, possibly near its confluence with the Camac and near the site of the early Scandinavian-style cemetery at Islandbridge and Kilmainham. The Scandinavian settlement may have been associated with an existing monastic site because the Viking burials seemed to be intermixed with Christian graves.

A settlement was re-established at Dublin downstream also on the south side of the Liffey at its confluence with the Poddle. This came after the brief early 10th century exile of the inhabitants from the initial settlement. This second settlement endured to become the walled town that was later Viking Age Dublin. Vikings raided Scotland, Ireland and England (dominating much of it until the Norman invasion) . Dublin was one of the early fortified bases established by Vikings in 841AD. Pagan Viking burials from the later 9th/early 10th centuries at Kilmainham and Islandbridge near Dublin, contained the personal possessions of the deceased. Warriors were buried with weapons including fine swords and the presence of weights, scales, purses, tongs and hammers suggests that some of the dead were merchants and craftsmen. Typically Scandinavian oval brooches, worn in pairs in women’s costume, as well as objects such as a whalebone ‘ironing board’, spindle whorls (for spinning wool) and bronze needle cases, tell us that Scandinavian women were also buried in these cemeteries.

With the expanse of Viking settlements, you’d expect there to be an abundance of Viking artifacts, and the museum has an amazing collection, from swords and other weapons, to jewelry, combs, toys, weighing scales for trading.

An ironing board (Vikings were tidy)

Vikings established fortified settlements along the river. This replica of a complete Viking settlement found near Christchurch shows how they lived. Semi rectangular structures with straw roofs, no interior walls and a hearth in the middle. There was no chimney, but a smoke hole (see the black ring in the center of these structures). This settlement was built along the river and had a wall – built to reduce flooding, but also to deter other invaders (there was a ladder they’d pull up from the river- see the gaps in the wall below). Houses in Viking Age Dublin had walls of post-and-wattle, which were probably daubed with cow dung or mud. Wood was used in house construction, ship building and furniture making, and was also used to make domestic utensils such as bowls, plates, cups and barrels, in addition to toys and board games. Wooden handles were fashioned for iron tools made by local blacksmiths, who also made hinges, hasps, locks, keys and harness fittings, while implements such as shovels and weavers’ swords were sometimes made of wood.

They traded using weigh scales and since there was no money, the “value” was “hack silver “ – silver they’d gained from their raids on monasteries.

What “happened “ to the Vikings? The Vikings eventually settled down in the lands they had conquered. By 950, the Vikings had stopped raiding in Ireland and developed instead as traders and settled in the lands around their towns. Although, in the battle of Clontarf, the native Irish defeated the Vikings and pushed them out of Dublin. It is estimated that between 7,000 and 10,000 men were killed in the one day battle, including most of the leaders. Although Brian Boru’s forces were victorious, Brian himself was killed, as were his son Murchad and his grandson Toirdelbach. Leinster king Máel Mórda and Viking leaders Sigurd and Brodir were also slain. After the battle, the power of the Vikings and the Kingdom of Dublin was largely broken. By that point, however, they had been fully integrated into Irish life, and most of them had converted to Christianity. The Viking Age in Ireland didn’t come to a definitive close until the Norman invasion in the 1170s and the last Norse king of Dublin fled to the Orkney Islands. There is a large proportion of modern Irish population that carries Scandinavian DNA, we also know this from clues in place names, street names, ruins and artifacts.

The second tour of the museum took us back to Mesolithic (middle Stone Age, 8000 BC – 4000 BC) Ireland , when Ireland was populated with hunter gatherers. They had a display of fishing traps made of reeds that had been buried in a peat bog (and were preserved by the anaerobic – lack of air) conditions (the artifacts are in a sealed case). During the Mesolithic , early humans began to figure out how to farm and domesticate animals, and they experimented with building small, permanent communities, but they still relied on hunting and foraging as well. It was during this time that early civilizations in Ireland built the Stone Age (Neolithic) megalithic monument called Newgrange (we visited in 2011) in the Boyne Valley, County Meath, it is the jewel in the crown of Ireland’s Ancient East. Newgrange was constructed about 5,200 years ago (3,200 B.C.) which makes it older than Stonehenge and the Great Pyramids of Giza.

The next rooms had displays in the period of the Bronze Age; the Bronze Age in Ireland lasted from around 2,000 to 500 BC. There were stunning displays of fine gold jewelry.

Though the tour didn’t take us through all of the “top ten” , we did get to see many of them- there’s so much to see.

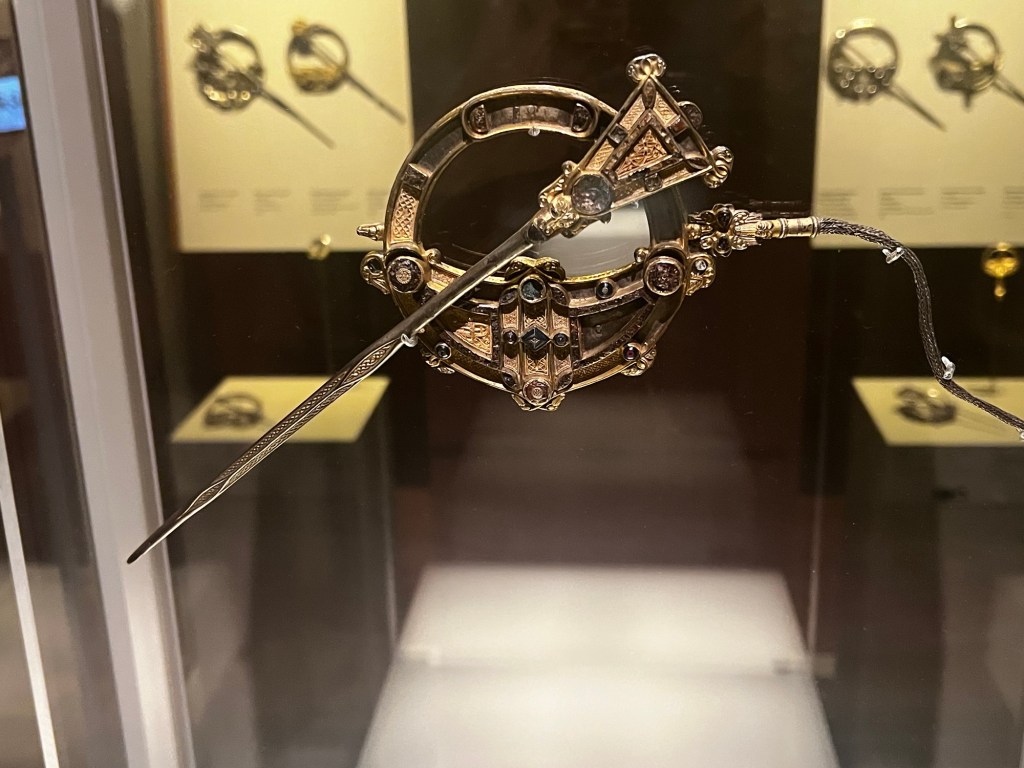

In early medieval Ireland, both sexes wore brooches to fasten their cloaks. The earliest iron or bronze examples were plain but later, finely decorated brooches were made with cast animal ornament and settings of glass and enamel. The finest known example of these highly decorated brooches is the 8th-century Tara Brooch.

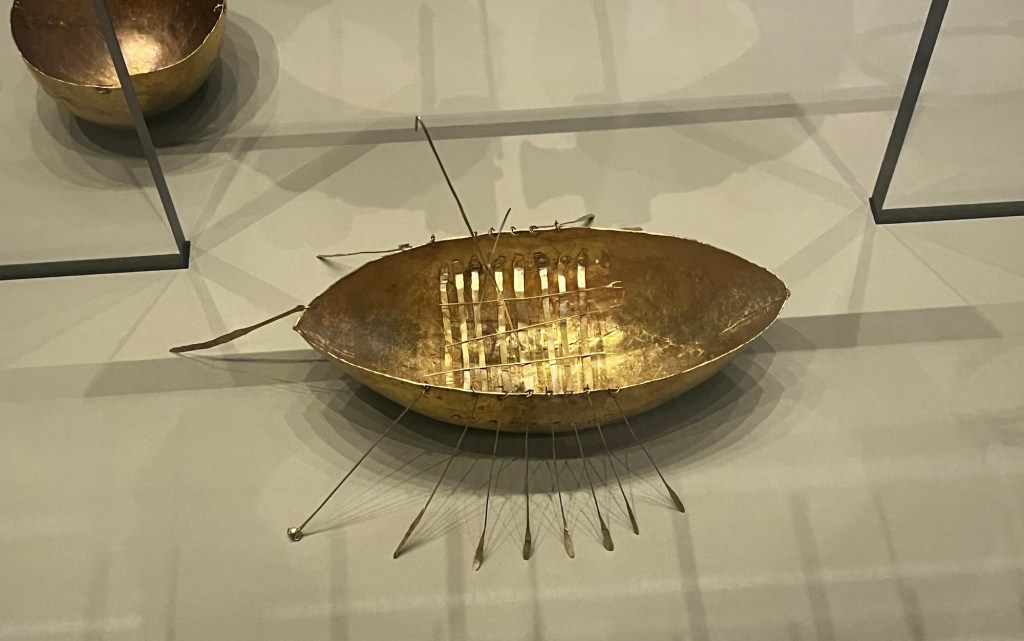

The Broighter Hoard

The hoard of gold objects from Broighter, County Derry, is the most exceptional find of Iron Age metalwork in Ireland. The tubular collar, miniature boat and cauldron, two neck chains and pair of twisted collars (torcs), which date to the lst century BC, were found on the ancient shore of Lough Foyle in Co. Derry. The sea god Manannán mac Lir was associated with Lough Foyle and the place-name Broighter (from the Irish Brú lochtair) may be a reference to his underwater residence.

Most notable is the model gold boat with its mast, rowing benches, oars and other fittings that can be regarded as an appropriate offering to a sea god.

The decoration on the tubular collar appears to include a highly stylised horse, an animal that is especially associated with Manannán mac Lir.

There were a number of “bog bodies “ on display, some only being partial bodies. Archaeologists were able to determine how they died (most very violently), what their approximate age at death was, and in some cases, what they ate before death.